The Samburu Tribe of Kenya: Culture, Traditions, and Modern Life

The Samburu are a tribe of indigenous people living in northern Kenya. They are semi-nomadic pastoralists, moving around to find grazing lands for their herds of cattle, sheep, goats, and camels. The Samburu are closely related to the Maasai and speak a dialect of the Maa language. They are known for preserving their traditional way of life despite modern influences. This article provides extensive information about the Samburu tribe, including their history, culture, traditions, religious beliefs, family roles, dress, customs, livelihood, challenges they face today, and places visitors can learn about or stay with the Samburu people.

Homeland and Population Size of the Samburu Tribe

The traditional homeland of the Samburu people is in northern Kenya in the Rift Valley Province. This is a hot, dry region not suited to growing crops. The Samburu have lived here for hundreds of years, herding their animals across the grassy savannah and scrub forests of this remote part of East Africa.

Currently there are an estimated 307,000 Samburu people living in Kenya. The largest concentrations of Samburu villages are found in the Samburu East and Samburu West districts of the Rift Valley. Many members of the tribe continue their traditional semi-nomadic way of life. However, some have recently settled into more permanent villages due to government pressure and lack of adequate grazing lands.

Cultural Similarities and Differences with the Maasai

The Samburu share deep cultural ties with the more well-known Maasai tribe. Both groups are nilotic ethnic groups originally believed to have migrated into Kenya from Sudan. The Samburu speak Samburu, a dialect of the Maa language that is similar but not identical to the language spoken by the Maasai.

In their oral histories, the Samburu say they are descendants of the Maasai. Some historical accounts say the Samburu separated from the Maasai in the 1700s due to a dispute over grazing lands. Others believe the Samburu formed as a distinct group earlier when part of the Maasai population migrated north into their present-day homeland. The Samburu refer to themselves as “loikop” meaning “owners of the land.”

Despite their common ancestry and many cultural similarities with the Maasai, the Samburu remain a distinct tribal group. There are small differences between Samburu and Maasai in their vocal intonation, clan organization, ceremonies, and women’s hairstyles and beadwork. However, to outsiders the two tribes mostly share a common East African pastoral culture focused on cattle herding.

Semi-Nomadic Pastoralist Lifestyle of the Samburu

The traditional lifestyle and culture of the Samburu tribe revolves around herding cattle across the grassy plains of northern Kenya. The Samburu are nomadic pastoralists who move their home settlements in search of fresh grazing areas and water sources for their animals.

A Samburu family’s wealth and status is measured by the size of their herds. A typical family may own 50 or more head of cattle as well as goats, sheep, donkeys, and sometimes camels. The main components of the Samburu diet come from these animals – milk, blood, and occasionally meat during ceremonies and special occasions. The herders depend completely on their livestock for food and transport. They view their animals almost as members of the family.

When grass and water start becoming scarce in an area, which happens every 5-8 weeks, the women dismantle the small, round houses made of mud, sticks, grass mats, and animal hides. The warriors help herd the cattle to new grazing grounds, sometimes walking over 15 miles in search of greener pastures. This mobile lifestyle means the Samburu must rebuild their villages frequently. It allows them to utilize seasonal grasses and water sources across a wide territory in the arid climate of northern Kenya. Their temporary settlements are called manyattas in the Samburu language.

At the center of each manyatta is an enclosure called a boma made of thorn brush. The boma provides protection and safety for the community’s livestock at night. During the day the cattle, camels, goats and sheep graze freely across the savannah grasslands and return in the evening for water, milking, and shelter inside the boma. The Samburu warriors guard the herds against attack from wild predators like lions, hyenas, leopards, and cheetahs which roam the African bush.

Small, Close-Knit Communities

In contrast to the individual homesteads of Maasai families, the Samburu live together in settled communities of relatives numbering 10-15 families. This allows them to pool their labor during times of drought or hardship. It also provides protection and collective defense against other hostile tribes who may try to steal their precious cattle.

The Samburu have very close community and family bonds. Each settlement functions like an extended family unit, caring for its members cooperatively under community rules and belief systems. Elders make most major decisions in the tribe. Yet everyone contributes insights before agreements are reached.

The Samburu villages practiced polygamy in past generations when resources could support multiple wives. But due to shrinking grazing lands, most men today can only afford to have one wife. Children are greatly valued in the culture as future herders to continue the family lineage and manage the ancestral herds when parents grow old.

Cultural Roles of Samburu Men and Women

There is a clear division of labor among Samburu tribe members based on age and gender roles:

Samburu Men and Boys

The Samburu men are considered warriors (murran) whose primary duty is to protect the community and livestock from harm. Young boys as young as five years old are assigned tasks like herding small stock to train them as future warriors. Around age fifteen, boys undergo a circumcision ritual to symbolize their transition into murran warrior status.

Following this rite of passage, young Samburu warriors live together in a “manyatta” built for unmarried men. During the day Samburu warriors walk for miles with the cattle as they graze. At night they keep guard while the animals are enclosed in the protective corral or boma. Elders teach the moran battle skills, hunting, animal husbandry, community laws, and important tribal history through oral stories and songs.

Samburu women construct the small, portable houses used by wandering groups of warriors. Yet strict cultural rules prohibit any intimacy or marriage between young Samburu warriors and women in their manyatta settlement. The warriors must remain celibate and vigilantly protect the tribe until they reach their late twenties or early thirties.

Only senior warriors who have proven themselves over 15-20 years or more can graduate out of moran status and become junior elders. At this time they may pay a dowry to take a wife, become heads of their own households, build their own manyattas, and start families.

Samburu Women

Samburu women have clearly defined domestic responsibilities including cooking, collecting firewood and water, milking animals, making butter and beads, tending small livestock around the village enclosures, caring for children, and building and dismantling houses when the community moves.

Girls learn to perform essential homemaking tasks at a young age from their mothers and other women. Around age thirteen, before reaching puberty, Samburu girls undergo ritual circumcision and face painful tests of courage to ready them for the duties of wife, mother, and central pillar of the home. Following this rite of passage to womanhood, they wear a leather skirt and tower of beads gifting by their father.

Once married, Samburu women take charge of their own house within the family’s shared domestic compound. The wife constructs her small, round mud and grass house. Here she home-schools children in tribal traditions, cooks meals, makes butter and beads, and tends the small livestock kept within the family boma for milk and meat.

Occasionally women accompany warriors grazing the herds, carrying gourds of milk and water on donkeys. But their primary domain is the manyatta around their own house. Several related wives may share childcare duties and household tasks. And as part of the larger community, Samburu women contribute insights and opinions around the village campfire where men gather to discuss major issues and decisions.

Traditional Beliefs of the Samburu People

The religious belief system of the Samburu tribe is centered around a single creator god called Nkai or Ngai. According to Samburu oral legends, Ngai exists alone in the sky but remains engaged in human affairs on earth. All cattle originally came from Ngai so the cow holds special religious significance. The Samburu attribute both good and bad fortune to the will of Ngai. They believe Ngai brings rain to fill water holes for their cattle, but also sometimes allows drought as punishment when people act wrongly.

Bad omens, hardship, illness or death befalling the community are believed caused by Ngai’s wrath due to breach of morality or tribal law. The Samburu follow strict codes of conduct to avoid such misfortune, enforced by elders, warriors, and spiritual leaders. Forbidden behaviors believed to provoke Ngai include incest, violating food taboos, eating certain animal organs, cheating the tribe, stealing livestock, killing snakes, or mistreating the natural world.

The Samburu spiritual belief system engrains deep respect for their natural environment. It forbids overusing or polluting water holes where wild animals must also drink. Their nomadic lifestyle prevents overgrazing in any one area so the grasslands can regenerate. And their pastoral existence fosters close observation and stewardship of the land over generations. Samburu legends say Ngai entrusted people as caretakers of the earth. So harmony with nature, as a manifestation of Ngai, remains integral to their culture.

Rituals Performed by Samburu Elders

The Samburu tribe places elders in high regard as teachers, storytellers, law enforcers, and spiritual mediators. Elders conduct all major tribal rituals for births, coming of age, marriages and funerals. During times of severe drought or difficulty, elders intervene to restore balance with Ngai.

One of the primary Samburu rituals for evoking divine favor is called “Lmuget” meaning “blessing.” The elders perform lmuget ceremonies at key junctures – severe drought, disease outbreak, death of an important tribe member, before raiding rival clans. First elders butcher a fat ram and spill its blood inside the villages’ sacred hut. Then they cut tree branches which women lean against their houses spread with white dung. Holding staffs, the elders bless the people and animals while walking sunwise around each homestead. Lmuget rituals reaffirm oneness between the Samburu community, their life-sustaining herds, and the beneficence of Ngai in restoring peace, abundance and wellbeing.

Colorful Samburu Tribal Dress and Adornment

Samburu tribespeople are easily distinguished by their very colorful style of dress, adornment and body painting. Samburu men and women both wear vivid red garments as their main clothing, accented by elaborate beaded jewelry. Women’s gowns and men’s warrior cloaks are made from 6-8 yards of commercial red fabric, preferably with strips of brighter shade alternating down the length. A leather belt cinches the cloth wrap in place.

Samburu women decorate their necks with spectacular collars made from thousands of tiny colored glass beads. These beaded necklaces drape down the woman’s torso in elegant strands, along with metal hoop earrings at the ears. Girls start helping make beads at young age – sorted, shaped, string together – to gift their brother when he graduates moran warrior stage.

Intricate patterns and designs get worked into women’s beadwork, each unique set receiving a poetic name like “ostrich plume” or “giraffe’s teeth.” Wives craft special beaded collars for their husband, using cowrie shells and geometric shapes as symbols of love, fertility and protection. A husband’s gift of an iron staff to lean on signifies his wife holds central place in his homestead.

Samburu men and male youth accent their red garb with smaller beaded accents on headbands, bracelets, waist straps and ceremonial sticks. But a Samburu warrior’s status is reflected most by his headdress. Senior elders wear folded red turbans, signifying wisdom and authority. Junior warriors crowns their shaved heads with caps of greased hair, gathered earth pigments, and ostrich feathers. This distinctly colorful Samburu tribal style immediately evokes a proud ancient culture when one encounters it.

Meaningful Songs and Dances of Samburu Tribe Life

The Samburu people integrate dance throughout their daily life and rituals. Expressive Samburu dances reinforce tribal unity and values through messages conveyed in the lyrics, beat, and symbolic meanings. Song and dance perpetuates their oral history across generations since the Samburu culture is not a written language.

Both men and women participate in community dances, with the warriors typically dancing in the inner circles and women in outer groups responding. However their dance formations remain separate because unmarried warriors and women are still barred from intermingling according to strict cultural norms of conduct.

Samburu dances feature group singing with clapping providing the rhythmic beat. Dancers may carry decorative sticks, swords or fly whisks made from cow tails with symbolic meaning. The moran warriors often perform a well-known “jumping dance” — jumping very high from standing position in unison while maintaining a steady cadence. Their dance movements act out events from Samburu legends or mime animals they protect.

The Eunoto dance remains the most sacred ritual dance of the Samburu tribe. It happens once every 15 years or so when a new age set of warriors graduates to senior elder status as a group. Lasting 10 days, Eunoto celebrations welcome the tribe’s new spiritual and governance leaders, emphasizing community solidarity under their authority going forward. All villagers join singing and dancing with great festivity and feasting during this time.

Threats to Samburu Tribe Culture and Traditions

For over 300 years the Samburu tribe has maintained its semi-nomadic pastoralist way of life in northern Kenya. Yet today their time-honored cultural traditions face real threats from pressures beyond their control. Loss of grazing lands, persistent droughts, government land policies, border security conflicts and lack of access to medicine or education challenge preservation of authentic Samburu heritage.

- Reduced Access to vital grazing lands and water has impacted Samburu migratory patterns for centuries. But prolonged drought and privatization of Kenya’s land for large-scale agriculture has drastically compounded this scarcity. Samburu settlements concentrate where vestiges of open savannah remain until grass totally depletes. Fights break out over contested land and water rights. Many must cut beloved herds or settle into permanent villages dependent on unstable jobs.

- Sporadic armed cattle raids from other ethnic groups like the Turkana, Pokot, and Meru put Samburu homes and youth at risk. Drought-related skirmishes date back generations as herders encroach each other’s dry season forage. Yet increased firearms traded for livestock since 1990s escalated raid fatalities tenfold. Samburu warriors now struggle defending families from machine guns using just spears. Over 200 die each year.

- The Kenyan Government provides little infrastructure, healthcare, school access or land rights to indigenous tribes like the Samburu. Officials consider their nomadic culture “backwards” and push sedentary living on communally-owned Trust Lands lacking economic options. Elders refuse fearing urban poverty and youth turning to crime. So families feel trapped balancing cultural identity against kids’ futures.

While holding fast to Samburu soul, creative new partnerships engage youth in schooling linked to pastoral life. Safari lodges channel tourism funds into bettering local communities. And activists lobby for indigenous land rights so herding families can sustainably manage their ancestral habitat. Blending old ways and new collaboratively works best securing Samburu heritage.

Places to Interact Meaningfully with the Samburu Tribe

For socially-conscious visitors hoping to engage respectfully with Samburu people, several award-winning eco-lodges provide that gateway. Revenue from these small-scale tourism partnerships support local Samburu livelihoods, culture and habitat conservation beyond cattle.

The Il Ngwesi nature conservancy, Lewa Wildlife Conservancy and Namunyak Conservancy started as efforts to save endangered species like rhinos. Their mission expanded supporting integrated human-wildlife coexistence models upholding Samburu pastoral culture. Foreign travelers can visit or stay at:

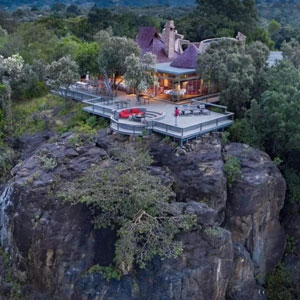

- Il Ngwesi Eco-lodge– Six private bandas (cottages) owned and staffed by local Samburu families. Guided nature walks give cultural insight. Funds build adjacent schools.

- Sarara community’s luxury tented camp – constructed sustainably by the Samburu who co-manage this nature conservancy safeguarding savannah habitat.

These ethical tourism partnerships let Samburu tribespeople welcome visitors to their beloved homeland themselves. The exchanges provide sustainable livelihoods and protect indigenous heritage. Travelers gain far richer perspective into authentic Samburu heart by listening and learning from them directly.

Showing 0 comments